Here’s the simple reason planes have winglets

Cabin looks like war zone and passengers hospitalised after really nasty turbulence

15/04/2016

Airline chief sued by own pilots for claiming ‘flying is easier than driving a car

07/05/2016Ever look out the window of a plane or watch as it pulls up to the gate?

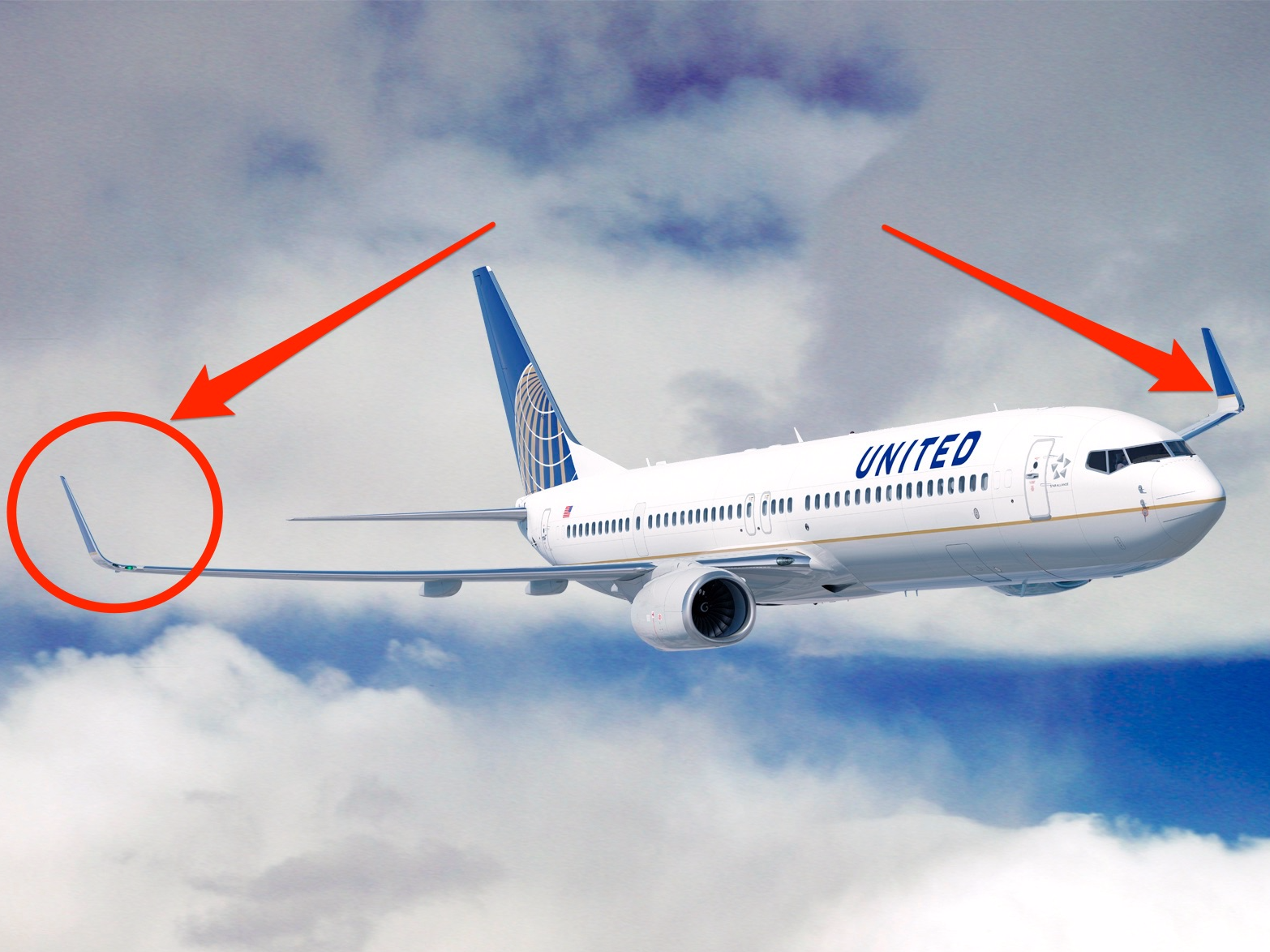

Have you ever wondered why some planes have pointy bits at the ends of the wings?

What you see are “winglets,” and they have essentially become standard equipment on all new airliners.

Why are they there?

“Winglets help reduce the drag associated with the creation of lift,” Robert Gregg, Boeing’s chief aerodynamicist, told Business Insider.

That’s the technical answer.

Gregg said the practical reason behind winglets is easier to comprehend.

Winglets allow the wings to be more efficient at creating lift, which means planes require less power from the engines. That results in greater fuel economy, lower CO2 emissions, and lower costs for airlines.

Boeing claims that winglets installed on its 757 and 767 airliners can improve fuel burn by 5% and cut CO2 emissions by up to 5%. An airline that installs winglets on its fleet of 58 Boeing 767 jets is expected to save 500,000 gallons of fuel annually.

Winglets help mitigate the effects of “induced drag.” When an aircraft is in flight, the air pressure on top of the wing is lower than the air pressure under the wing. Near the wing tips, the high-pressure air under the wing rushes to the lower-pressure areas on top, which results in the creation of vortices. The vortices flow in a three-dimensional manner over the wings. They not only pull air up and over the wing, but they also pull air back. That third component is induced drag.

With the advent of winglets, the aircraft is able to weaken the strength of wingtip vortices and, more important, cut down on induced drag along the whole wing.

(Dragan Radovanovic/Business Insider)

Induced drag can be overcome by making the wing longer.

In fact, the general rule is, the longer the wingspan, the lower the induced drag, Gregg said.

But in many instances, airplane makers simply don’t have the option of making the wings longer. For example, narrow-body airliners such as the Boeing 737 and 757 often operate from gates at airports designed for short- to medium-range domestic flights. Since these flights usually require smaller aircraft, they have less room apportioned to them. As a result, wingspan is effectively limited by the size of the parking space the plane is allotted at the gate.

So instead of the adding wingspan by making the wings longer, Boeing adds wingspan by going vertical with winglets.

In some instances winglets aren’t necessary, because there are no constraints on space. For example, Boeing’s hot-selling 777 wide-body airliner does not have winglets. According to Gregg, that’s because the 777 operates from international terminals designed for larger jumbo jets. As a result, Boeing found the performance it was seeking without the need for vertical extensions.

(Boeing)

A Boeing 777. No winglets here.

Since they were first developed by Richard Whitcomb at NASA’s Langley Research Center in 1976, airplane makers have steadily worked to improve the design and effectiveness of winglets.

According to Gregg, the first-generation winglets fitted to aircraft such as the Boeing 747-400 and the McDonnell Douglas MD11 offered up to 2.5% to 3% improvement in fuel burn compared with aircraft not equipped with the option.

Second-generation winglets, such as those found on Boeing’s workhorse 737, 757, and 767 aircraft are much larger than the first-gen models, with greater curvature. Second-generation winglets offer a 4% to 6% improvement in fuel burn.

Boeing’s new 737 Max airliners are equipped with third-generation winglets that offer a 1% to 2% improvement over the second-gen models.